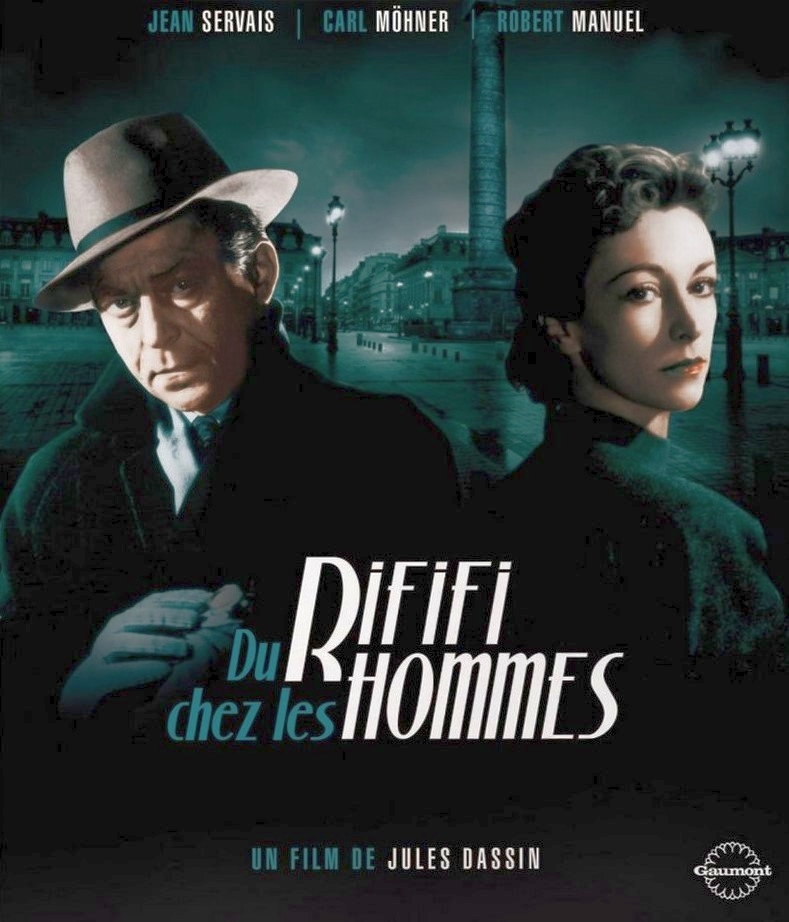

“RIFIFI”

Du Rififi chez les hommes

Film Noir Heist Thriller

Winner, Best Director,

Cannes Film Festival

“The best film noir I have ever seen.” — Francois Truffaut

Director Jules Dassin, France, 1955, 118 min., in French with English subs.

Rental fee $10 per household

Three-day streaming window

Livestream Film Discussion –

Monday, 28 September, 7 pm

Dr. John Alberti, Chair, Department of English & Director of Cinema Studies, NKU, will lead the discussion. Register: Zoom via CWC Facebook.

If you missed this, contact us for a link to the recorded discussion when you rent the film.

Rififi’s white-hot suspense seamlessly crackles with excitement. As he had done for San Francisco (Thieves’ Highway), New York (The Naked City) and London (Night and the City), Dassin turned Rififi into a sort of cinematic city symphony, revealing a broodingly beautiful Paris most French directors had always overlooked.

Esteemed auteur Francois Truffaut tells us that “Everything in Rififi is intelligent: screenplay, dialogue, cinematography, sets, music, choice of actors. The direction is a marvel of skill and inventiveness.”

About the Film

RIFIFI (ri-fí-fi) n. French slang. 1. A quarrel, rumble, free-for-all, rough-and-tumble confrontation between individuals or groups. 2. A tense and chaotic situation.

In his essay for Criterion, Jamie Hook shares why Rififi is a terrific viewing experience:

Part of the key to Rififi’s genius is that no single element outshines another. Like a diamond, each facet of the film gleams as brightly: The performances, especially Jean Servais’ minimalist take on the dog-eared protagonist Tony and Dassin’s own lighthearted portrayal of the safecracker Cesar le Milanais (under the pseudonym Perlo Vita), are quite excellent. The cinematography is stunning, particularly the nighttime shots, where we see the shape of Tony’s hat laid against the smears of neon that pulse in the city streets behind him. The music, by famed composer Georges Auric, is dead on, restrained and somber, occasionally breaking into dance.

The plot is an economic wonder: three succinct acts that unfold with the dedication of an opera, building to a glorious, dramatic finish. And the sets, by the great designer Alexandre Trauner (who had worked on Children of Paradise), manage to hold their own against Dassin’s obsessively and lovingly researched street locations. The interior of the obligatory gangland nightclub (named “L’Age d’Or” in homage to the Buñuel film) is especially handsome, its definitive architecture piling the requisite layers upon layers—like the ballroom leading upstairs to the gangster’s office, which, of course, has a back door that takes us to the dreamland of backstage. Only the gorgeous Parisian locations—the train station and assorted back alleys—threaten to outshine Trauner’s lovely sets.

And yet, even in a film of such generous superlatives, something does stand out, towering over it all. For Rififi is that most hallowed of films, a film that contains a monument within. Like the Grand Hall ball in The Magnificent Ambersons or the pickpocketing sequence in Pickpocket or the crop-duster chase in North by Northwest, the virtually silent, gleefully long heist scene at the center of Rififi is a tingling, ecstatic, sustained act of brilliance. For an astounding 33 minutes, Dassin removes all dialogue and music, hushing the soundtrack to the mere sounds of breath—as we observe the criminal team at work, breaking through the floor, silencing alarms, cracking safes, checking watches, and signaling each other.

It is a scene you’ve seen before (imitators have been cannibalizing it for decades), but you will never see it so purely, respectfully done as here. The fetishistic shots of the safecracker’s tools, the rope that comes out of the suitcase already knotted and ready for climbing down, the team’s proprietary language of hand-gesture, the justly famous conceit of the umbrella—all of these elements are so lovingly described, it makes you want to cry out.

But it is the simple image of the men working together that binds it all. The film may be about crime, but at its heart, Rififi reveals itself actually to be a paean to work—not the drudgery of labor, but the poetic “Love Made Visible” that Khalil Gibran once described. In these 33 glorious minutes, we see our heroes as they were meant to be: working together.

Production Notes

These notes come from Lenny Borger via conversations with Jules Dassin in 2000. After 12 years as a Variety critic he found his passion: he’s famous for his translation and subtitles for French films, work that has included Jean-Luc Godard’s “Breathless,” Jules Dassin’s “Rififi” and Jean Renoir’s “La Grande Illusion.” He is also a cinema detective, searching for, and restoring, films thought to be lost. Henri Fescourt’s 1929 silent epic “Monte-Cristo” is among those finds.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When Jules Dassin directed Du Rififi chez les hommes in Paris in 1954, he knew it was probably his last shot at making a film comeback after being named as a communist before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1952.

The long arm of McCarthyist America had successfully crushed several earlier attempts by Dassin to rebuild his shattered film career in Europe. The most notorious example of this transatlantic persecution came in 1953, when the producers of a new vehicle for comedian Fernandel, Public Enemy No. 1, fired Dassin as director just days before he was to begin shooting. The incident became a cause célèbre in France, where an industry support group was led by Jacques Becker (shortly to direct his own seminal gangster opus, Touchez pas au grisbi).

Months later, Dassin was in Rome, working on an adaptation of Giovanni Verga’s Sicilian literary classic, Mastro don Gesualdo, but it was sabotaged via interference from the American Embassy. It was there that Dassin received a call from an agent asking him to return to Paris to meet producer Henri Bérard, who had acquired the rights to a best-selling crime novel by newcomer Auguste Le Breton, Du Rififi chez les hommes. Dassin’s Naked City had been a major success in France and Bérard flattered Dassin by saying no one else but Dassin could do Rififi.

But there was a major obstacle. “I got along in French, but the book’s slang was a new language, ” Dassin recalls. “So I called an agent friend, Claude Briac, and asked him to come over and translate it for me. It was a weekend, Friday or Saturday, and I had to give the agent my answer on Monday. But Briac had been courting the same dame for years and she’d finally promised to meet him that Sunday. But I said, ‘No, come and read to me.’ And the poor bastard did!”

Dassin admits he loathed the novel. He was repelled in particular by the story’s inherent racism: the rival gangsters pitted against the story’s heroes were Arabs and North Africans. “I was appalled. They were doing all kinds of horrible things, not stopping at necrophilia. On Monday I went to the agent intending to tell him, ‘I can’t do this!’, and instead I heard myself saying, ‘Oh, yeah, I want to do it!’ I needed the work.”

Working under pressure, Dassin wrote the screenplay in six days (veteran screenwriter René Wheeler then helped rework the material back into French). Dassin built up the friendship between Tony the Stéphanois and his protégé Jo the Swede and downplayed the turpitude of the rival gangsters who became Europeans with the more Germanic- sounding name of Grutter.

More importantly, he devoted quasi-documentary attention to the actual jewel heist, which was a mere 10-page throwaway early in Le Breton’s 250-page source novel. “That was the only way to work my way out of a book that I couldn’t do, wouldn’t do.” In the final film, the caper would take up a quarter of the film’s two-hour running time and become a classic set piece, which would spawn innumerable imitations.

As might be expected, Dassin’s screenplay displeased Le Breton, whom the producer had hired to write the dialogue. “Le Breton was really a character. I believe he had done time in jail or reform schools. And he loved to play the gangster as he saw the gangster played in American movies, with the hat and the manner. I found him rather amusing. When he read my script, he came to see me and said: “Where’s my book?” I tried to explain that’s how it is when you adapt a book, and he took out a gun and plunked it down on the table, and repeated, “Where’s my book?” I looked at him, I looked at the gun and I began to laugh. And because I laughed he took me in his arms and we became friends.”

As he had done for San Francisco, New York and London, Dassin, with the aid of cinematographer Philippe Agostini, turned Rififi into a sort of cinematic city symphony, revealing a broodingly beautiful Paris most French directors had always overlooked. “I remember walking the streets of Paris and dictating to a secretary, ‘We’ll do this scene here and this one there, just really improvising as we walked. When you make a picture, and you do locations, you gotta walk.’”

Working with what he remembers to be a risible $200,000 budget, Dassin could not afford stars (as Becker could in Touchez pas au grisbi, which owed much of its success to Jean Gabin). He had to make do with second-best but the lack of major names above the title served the film’s gritty realism. The tubercular and world-weary Tony the Stéphanois was memorably acted by the Belgian-born Jean Servais (1910-1976), who had been in pictures since the early talkies but whose career had gone into a slump due to drinking problems. Servais’s ravaged looks and deep melancholic voice gave Tony a tragic grandeur that made one critic call Rififi a “Greek tragedy in Pigalle.”

The high-spirited Italian gangster Mario Ferrati (a cynical pimp in Le Breton’s novel) was played by Robert Manuel (1916-1995), a beloved member of the Comédie-Française, where Dassin saw him in one of his specialty comic roles. As Jo the Swede, Dassin, acting on a suggestion by the producer’s wife, cast Carl Möhner (1921-2005), a young Austrian-born stage and screen actor. (Both Servais and Möhner would work again under Dassin’s direction in his next film, He Who Must Die, again produced by Bérard).

Using the pseudonym Perlo Vita, Dassin himself stepped into the shoes of César the Milanese, the Italian safecracker whose weakness for women unleashes the tragic chain of bloodletting. “We had cast a very good actor in Italy, whose name escapes me, but he never got the contract! When I called him, on a Thursday, I think it was, and we were shooting on Monday, he said he was wrapped up in another film. So I had to put on the mustache and do the part myself.”

Among the supporting cast were two young players whose careers were launched by Rififi. The slangy “Rififi” theme song was delivered by Magali Noël (1931-2015), one of the most popular sex kittens of French and Italian films of the 50s and 60s (she would later become a favorite Fellini icon in the maestro’s La Dolce Vita, Satyricon and Amarcord). As for young stage actor-director Robert Hossein (born 1927), who played the razor-wielding junkie Rémi Grutter, it was the beginning of a long line of violent sociopaths and brooding anti-hero roles, before he abandoned the cinema for the stage.

If Dassin’s cast was not bankable box office, his technical collaborators were the cream of the crop. In addition to cameraman Phillippe Agostini, he also had “one of the greatest men in the history of cinema”: production designer Alexandre Trauner, whose credits had included everything from Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or (which has an homage in Rififi as the name of the nightclub) to the staggering sets for Marcel Carné’s The Children of Paradise. Because of his reputation as a perfectionist, says Dassin, Trauner had done little of real import locally since the costly fiasco of Carné’s first postwar film, Les Portes de la nuit. Eager to demonstrate he was not a ruinous collaborator, and out of friendship for Dassin, Trauner did the sets for Rififi for “almost nothing.” (Trauner later had an even more successful career in Hollywood, where he designed several films for Billy Wilder, including The Apartment.)

Dassin’s other great artistic collaborator was composer Georges Auric, who had written one of the first great sound scores for René Clair’s A Nous la liberté. But at first Dassin and Auric could not agree on the scoring of the famous caper scene. “Auric was a wonderful guy. When I said I didn’t want any music during the big caper scene, he and Bérard went nuts. Auric said: “Look, I’ll tell you what, I’m going to protect you, I’m going to write the music for the scene anyway, because you need to be protected.” And he went and scored the entire sequence! When the film was all done, I called him and said, ‘I’m going to run the film for you, once with the music and once without.’ And afterwards, Auric came out and said: “Get rid of the music!”

Upon Rialto’s acclaimed re-release of the film in 2000, Dassin admitted that he somewhat regretted the Rififi theme song, which parodies the underworld slang Le Breton helped introduce into French gangster movies of the 50s. Although nightclub numbers were a convention of film noir of the 40s and 50s, the song was really to explain to audiences the meaning of the film’s title, “Rififi,” which ironically, is never uttered by any of the characters. It was written in two days by lyricist Jacques Larue and composer Philippe-Gérard after Dassin nixed a proposal by Edith Piaf-collaborator Louiguy (the author of “La Vie en rose”). Dassin had also interviewed a young songwriter-singer who was struggling to overcome the handicaps of a sickly-looking appearance and strange voice. Bérard told Dassin not to bother with him, that he wouldn’t come to anything. Dassin complied. The songwriter was Charles Aznavour.

Dassin remembered the film being made in “a marvelous atmosphere of friendship. My problem was that I hadn’t made a film in such a long time I was terribly nervous in the beginning and I had to fight for people not to see it. The only serious tensions came from the producer because I didn’t want to shoot in sunlight, I waited for gray days, which may have extended shooting time. It drove him mad.”

Amusingly, Bérard was also frustrated by the film’s lack of… “rififi!” The big man in French commercial pictures at the time was Yank expatriate singer-actor Eddie Constantine, who was then starring in a hugely successful series of comedy thrillers as Lemmy Caution, the quick-fisted, hard-drinking G-man imagined by British crime novelist Peter Chesney. “Bérard insisted that I throw in scenes of fist fights like in the Constantine pictures. He’d keep insisting, ‘Where are the fights, where are the fights?’ and I’d say, ‘Well, next week, next week!’

Against all odds, Du Rififi chez les hommes was a smash hit from its Paris first-run in April 1955, a success ratified that same month when the jury at the Cannes Film Festival awarded Dassin the directing prize. Dassin’s reputation was restored, along with his financial situation: with Bérard unwilling to give him anywhere near a decent salary, Dassin had agreed to a percentage of the box office take!

Despite the ignominious attempts from Hollywood & McCarthyites to stop Dassin from working, Rififi enjoyed an enviable art house career in the United States, first in a subtitled version, then in a dubbed re-release (re-titled “Rififi…Means Trouble!”). Typically, the film did draw fire from the Roman Catholic Legion of Decency, which slapped a C (“condemned”) rating on it, but after three brief cuts and the addition of an opening title card consisting of a quote from the Book of Proverbs, Rififi was upgraded to the B category (morally objectionable in part).

The Rialto Pictures re-release is of the original, uncensored version. The Rififi adventure had a curious minor coda years later, when Dassin ran into director Jean-Pierre Melville one day in Paris. “Melville virtually cold-shouldered me. It was only afterwards that I found out why: He had been promised Rififi chez les hommes but Bérard had double-crossed him!” Melville exorcised this early professional disappointment in 1969, when he directed his most successful film, Le Cercle Rouge, a highly stylized makeover of the Rififi story, which included a long, silent caper centerpiece.

About the Director

JULES DASSIN (Writer/Director)

Born Julius Dassin, on December 18, 1911, in Middletown, Connecticut, one of eight children of a Russian-Jewish immigrants Samuel Dassin and Berthe Vogel. In the twenties, he moved with his family to the Harlem section of New York City and attended Morris High School in the Bronx, graduating in 1929. After drama studies in Europe, in the mid-thirties he returned to New York and became an actor with the ARTEF Players (Arbeter Teater Farband). Dassin played character roles in Yiddish, mainly in the plays by Sholom Aleichem. and was a member of the troupe until 1939. But upon discovering “that an actor I was not,” he switched to directing and writing. Around that time, he joined the Communist Party of the United States, but after a few months left the party in 1939, disillusioned when the Soviet Union signed a pact with Adolf Hitler.

Dassin developed his writing skills in New York, creating radio scripts. In 1940 he went to Hollywood, as an apprentice director at RKO, working for Alfred Hitchcock during the shooting of Mr. And Mrs. Smith and also for Garson Kanin. Soon after, he began directing shorts for MGM and one of these, an Edgar Allen Poe adaptation, The Tell-Tale Heart (1941), resulted in his promotion to feature director.

Although his early films boasted big stars like Joan Crawford, Conrad Veidt, John Wayne, and Charles Laughton, his MGM pictures were mildly entertaining suspense and comedy fare, although the Laughton film, The Canterville Ghost, was a significant hit.

In the late 40s he seemed to have at last found his stride with three dynamic on-location slice-of-life dramas, Brute Force, The Naked City (a groundbreaking crime drama shot on the streets of New York), and Thieves’ Highway (shot on location in the streets of San Francisco), that earned him renown in Europe as the first American “neo-realist.”

Just as he was gaining recognition as a director with something to say and an interesting way of saying it, he was forced into exile in Europe as a result of the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings, in which he was identified as a Communist by Edgar Dmytryk.

Studio head Darryl F. Zanuck sent Dassin to England, where he directed another intelligent film in his newfound semi-documentary style, Night and the City, shot on location in the streets of London. With the cloud of McCarthyism looming, Zanuck advised Dassin to “shoot the expensive scenes first, to hook the studio” so the film was finished and released in 1951. Dassin was subpoenaed by the HUAC in 1952 and eventually became blacklisted after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. As a result, it was five years before he would direct another movie.

He left the United States for France in 1953 and struggled during his first years in Paris. He was not fluent in French, and his connections were limited. Moreover, the political influence of the McCarthyists crushed Dassin’s initial attempts to rebuild his film career in Europe. Two films, Public Enemy No. 1 and Mastro don Gesualdo, were cancelled due to interference by the American Embassy with threats that a Dassin film would never screen in the United States.

Eager to work, Dassin accepted a low-budget film, Rififi in 1954. He completely rewrote the screenplay and induced top-notch filmmakers to work for little or nothing. This suspense gem was a box office hit and Dassin won the Best Director Award at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival. While accepting the award at Cannes, he met the woman who would become his muse and second wife, the Greek actress Melina Mercouri.

He began his Greek period in the 1960s with several entertaining films starring Mercouri, the best known of which, Never on Sunday, discovered the Greek isles for Americans, won an Oscar for its memorable theme song, and a Best Actress award at Cannes for Mercouri. Another commercially successful venture, Topkapi, was a colorful and highly entertaining jewel-robbery caper.

Dassin produced and co-scripted most of his own films since 1950. He also appeared in several as an actor, sometimes using the pseudonym Perlo Vita. From 1980, he was active as a theater director in Athens, where he lived on Melina Mercouri Street and ran the Melina Mercouri Foundation. Dassin died in Athens on March 31, 2008 at age 96.

Accolades & Reviews

Cannes Film Festival (1955)

Winner, Best Director (Jules Dassin)

Nominee, Palm d’Or (Jules Dassin)

French Syndicate of Cinema Critics (1956)

Best Film (Prix Méliès)

National Board of Review, USA (1956)

NBR Award, Top Foreign Film

New York Film Critics Circle (2000)

Special Award for the re-release

~~~~~~~~~~

“The best film noir I’ve ever seen.” – François Truffaut

“Jules Dassin’s ‘RIFIFI’ remains the best of all heist movies.” – Alan Scherstuhl, The Village Voice 2000

“One of the great crime thrillers, the benchmark all succeeding heist films have been measured against, a driving, compelling piece of work, redolent of the air of human frailty and fatalistic doom.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times 2000

“It took an experienced US director, Jules Dassin, who has lived in France some years, to give the French gangster pic the proper tension, mounting and treatment. This pic has something intrinsically Gallic without sacrificing the rugged storytelling.” – Variety 2007

“It’s one of the most important movies of the 20th century, and one of the very best.” – eFilmCritic.com 2000

★★★★! “THE FRENCH CRIME THRILLER THAT BROKE THE MOLD!” – Jami Bernard, New York Daily News

“The underworld equivalent of a sublime French meal.” – Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly 2000

“Makes the characters in Mickey Spillane seem like sissies… This is perhaps the keenest crime film that ever came from France … but there is also a poetry about it … Has a flavor of crooks and kept women and Montmartre ‘boites’ that you can just about smell.” – Bosley Crowther, New York Times 1956

“One of the greatest crime movies ever made.” – Phillip French, The Guardian 2000

“Possibly the best heist noir ever made.” – Michael Phillips, Chicago Sun Times 2000

“An impeccably crafted piece of entertainment.” – Urban Cinefile 2000

“The underworld romance of Rififi’s Paris has an undeniable and timeless appeal.” – Gordon Bass, Filmcritic.com 2000

“Flawless! For lovers of tough-guy movie making, RIFIFI means perfection.” – Michael Sragow, The New York Times 2000

★★★★! “Among the picture’s many surprises is a superb robbery scene filmed in a near-total silence that contrasts exhilaratingly with the noisy flamboyance of more recent films in this venerable genre.” — David Sterritt, Christian Science Monitor 2000

★★★★! “THE FRENCH CRIME THRILLER THAT BROKE THE MOLD!” – Jami Bernard, New York Daily News 2000

“Indubitably the best underworld story yet filmed…If you crave an underworld story that will hold you in an iron grip, Rififi shouldn’t be missed. In our opinion, it is the best foreign film seen this year.” — Justin Gilbert, Daily Mirror 1956

“Rififi contains a 30-minute stretch of wordless movie making that is one of the most engrossing sequences since the invention of talking pictures…. [Dassin] gathers enough honors in this memorable silent sequence to satisfy most writers, directors and actors for a lifetime of work.” — Time 1956

0 Comments